Evidence Review case study: SolidarMed

An evidence review for a housing program in rural Zambia helped the nonprofit SolidarMed

a) understand the strengths and weaknesses in its theory of change, b)identify areas for further investigation through a monitoring, evaluation, and learning system, c) create a database in which to enter new research pertinent to its program.

Background

Delivery of health services in rural Zambia is critical; over half the Zambian population lives in these areas and they shoulder a heavy burden of disease. However, a shortage of healthcare workers willing to work in rural areas hampers delivery of health services and, ultimately, positive health and health systems outcomes. Rural areas struggle to attract and retain healthcare workers, in part because of inadequate housing options. To address this challenge, SolidarMed runs a program to construct and renovate housing for healthcare workers in rural areas. By improving the quantity and quality of housing for healthcare workers, SolidarMed aims to alleviate staff shortages, with the hypothesis that this will translate into improved health outcomes in rural Zambia.

Question

SolidarMed sought to clarify its pathway to impact – what conditions needed to hold for the housing program to lead to improved health outcomes? To answer this question, IDinsight:

- Produced a theory of change for the housing program

- Conducted an evidence review to understand whether and in what ways research supported the pathway to impact laid out in the theory of change, as well as to identify gaps in the existing literature

The rest of this case study focusses on the evidence review for SolidarMed’s housing program. For more information on the process of creating the theory of change for this program, please click here.

Approach

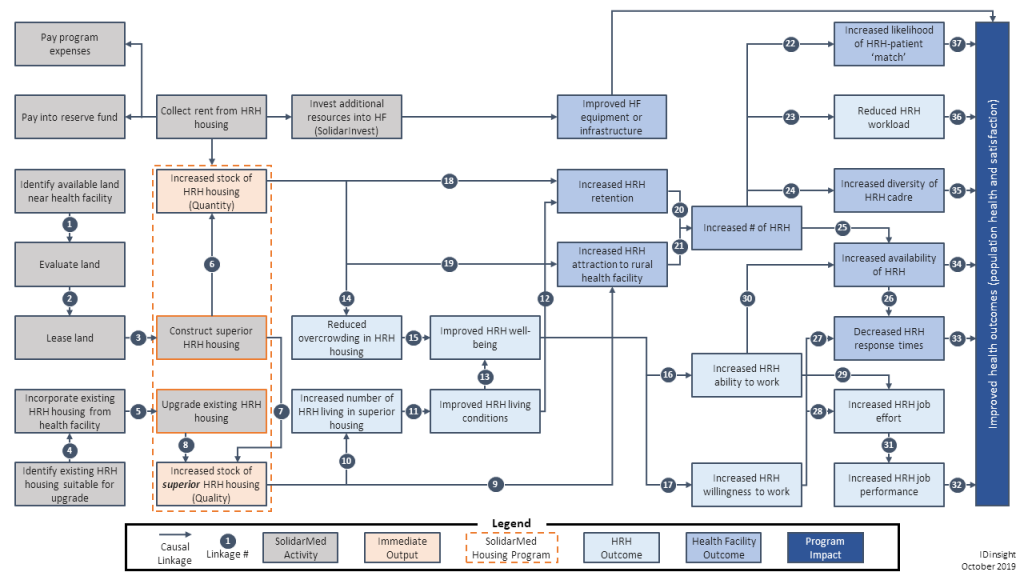

Reviewing the literature helped us a) develop the theory of change (below), and b) assess the likelihood that the theory of change would hold.

Searching for evidence

We first looked for studies linking superior housing for healthcare workers to health outcomes. Unfortunately, no such evidence was available, mainly because few large-scale programs had been implemented and evaluated. We thus decided to explore the evidence for critical assumptions in the theory of change, specifically:

- How superior housing influences the attraction and retention of healthcare workers to rural areas

- How general housing influences the attraction and retention of healthcare workers to rural areas

- How superior housing affects the well-being of occupants

- How attraction and retention of healthcare workers leads to improved health outcomes. More specifically, we investigated how improved performance by healthcare workers could lead to improved health outcomes

- How health facilities and rural infrastructure lead to improved health outcomes

We primarily used Google Scholar to search for keywords relevant to each link in the theory of change.

Overview of evidence found

- Evidence suggested that poor housing dissuades healthcare workers from moving to and staying in rural areas

- There is also compelling evidence that a sufficient rural health workforce can contribute to improved rural health outcomes

- Although there is no evidence on the isolated effect that improved housing has on health systems outcomes, there is evidence supporting some of the linkages between superior housing and improved health outcomes.These pathways include the link between improved housing and healthcare worker living conditions.

- However, there is little to no evidence for other potential linkages between superior housing and improved health outcomes. For example, at the time of this review there was little evidence on whether an increased number of healthcare workers in a rural area will consistently lead to increased availability of healthcare staff in the relevant clinic

Synthesizing the evidence

Based on the evidence, we assessed the likelihood (high/medium/low) that each assumption held. We also noted the assumptions for which there was no evidence from the literature.

Results

A simplified version of SolidarMed’s theory of change is given below.

The evidence substantiating the first link in this theory of change is relatively strong. It is logical to conclude that SolidarMed’s housing program may have a positive impact on retention of healthcare workers, which could lead to more health staff on-site for longer periods of time.

The evidence in support of superior housing affecting patient health outcomes is weaker. This pathway to impact operates through multiple channels. Evidence suggests that some of the ways housing could lead to improved health outcomes (for example, through increased availability of healthcare workers and reduced workloads) may hold, but other pathways like increased diversity of the cadre of healthcare workers may not hold or are relatively unexamined. In other words, housing may impact patient health outcomes through some channels and not others.

Overall, the theory for SolidarMed’s housing program is convincing. Given the evidence, it is reasonable to conclude that superior housing likely has an impact on the number of on-site health staff (mostly through retention). An increased number of on-site health staff may lead to improved patient health outcomes through one of many impact pathways, if the corresponding assumptions hold.

In order to confidently conclude whether superior housing leads to improved health outcomes, we recommended that SolidarMed test key assumptions and linkages in its theory of change, through the development of a monitoring, evaluation, and learning system. This is a key step towards eventually measuring the causal impact of the housing program with an impact evaluation.

The evidence review continues to serve as a ready reference for literature relevant to the program. It also provides a structured database that SolidarMed can easily update with new research relevant to its program.

Explore more examples from IDinsight projects

Guide

Not sure where to go from here? Use our guide to frame a question and match it to the right method.

Evidence review?

Want to learn more about evidence reviews, Click here to find out more.

Create your theory of change

Use our drag-and-drop tool to create a theory of change diagram