About the theory of change

Every development program rests on a theory of how and why the program will work and lead to social impact. A theory of change formalizes this, representing how a program will use resources to conduct activities that can lead to changes in behavior and improvements in people’s lives.

Whether you are designing programs, tracking program implementation, or measuring impact, a theory of change lays out the steps necessary to achieve your goals. It is also the blueprint based on which you will decide which evidence-generation tools to use. We thus strongly encourage all organizations to map out a theory of change for each of their programs to ensure teams have a shared vision of success. A theory of change is a living document that should be maintained – we also encourage teams to regularly revisit their theory of change, to make sure it reflects their current understanding of the program and its context.

Example

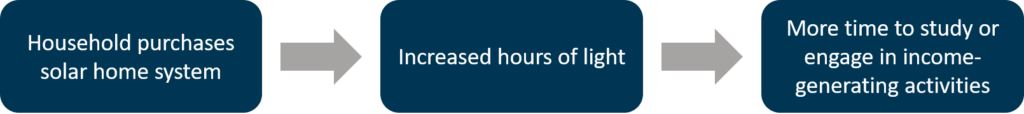

A very simple theory of change for a business selling solar lighting systems might be:

My program will help increase incomes by selling solar home systems that allow households to have light and electricity in the evening. [1]

Represented in a diagram, that same theory of change might look like this:

Even this simple narrative helps us frame important questions about whether the program is likely to be successful:

- Do we know if households that lack electrification are interested in buying solar home systems?

- Are we confident that the solar home system provides more light than kerosene lamps?

- Do households actually use the extra hours of light for studying and income-generating activities?

- Is studying supposed to increase income, or are educational outcomes a separate objective not yet explicitly stated?

Note that while even a simple theory of change helps frame important questions, the theory of change you develop should reflect your program and will often be more complex.

[1] Loosely based on the theories of change for home solar providers d.light and M-KOPA

Why you should develop a theory of change?

A theory of change encourages critical, creative, and empathetic thinking on how the world works and how programs may work, or fail to work, in that world.

When all program activities and expectations about your impact are written out in a theory of change, it is easier for program staff to align on how the program should run. For instance, in our solar home program, staff may face tough decisions about whom to prioritize: households that have an at-home business or households with school-aged children? We have found that it is quite common for an organisation’s members to not be aligned on the priority objectives of their program. And when left implicit, this causes confusion. Developing a theory of change helps your team articulate these questions and make decisions in keeping with your organization’s values and goals.

A theory of change allows you to clearly describe the pathways that will lead your program to success – which, in turn, leads to a better-designed program. For example, a program to reduce malaria by distributing bed nets rests on multiple assumptions, including that recipients will use bed nets correctly after receiving them. Documenting this through a theory of change may lead you to realize that you need to investigate whether and how the bed nets are used after distribution, and possibly do more to explain their importance to recipients.

A theory of change will help you identify the steps that are essential for your program to be successful and should, therefore, be tracked with data. Using the previous example of the solar homes program, a theory of change may reveal that you are assuming that recipients do not have existing cheap sources of light, or need extra hours of light, and that is why they demand solar lights. Since this assumption is critical to the success of your program, you decide to measure recipients’ demand for light and check how it relates to purchases. Thus, by serving as a concrete representation of your program’s steps and assumptions, a theory of change can help you figure out where you need more evidence.

All the methods in the Impact Measurement Guide rely on a theory of change as a starting point, from deciding which assumptions your program can safely make based on existing research (evidence review), to assessing the strength of other assumptions (process evaluation), to deciding which critical activities you need regular data on (monitoring). This is also why a theory of change must be revisited regularly, to make sure it is in sync with the reality on the ground.

Documenting your program activities and the steps by which these activities lead to impact can help you better describe your program to donors and supporters.

How to draft a theory of change

- What is the goal that the program wants to achieve?

This is the long-term objective or “ultimate outcome” of the program. Your program might strive to achieve some improvement in livelihood related to education, health, and economic outcomes of individuals. Example: A program that reminds parents to get their children vaccinated against malaria at upcoming vaccination camps may list “Improved children’s health outcomes” as its ultimate outcome. - What does the program do?

These are the activities directly conducted as part of the program. You should be as comprehensive as possible when listing the activities. Even preparatory activities (e.g., getting the list of households without vaccinated children) should be included. For clarity, it is also helpful to identify the personnel/stakeholder doing the activity. Example: The vaccination reminder program may identify “Program Team [Who] sends the reminder text about the vaccination camp [does what] to parents [with whom/with which frequency]” as an activity. - What are the products or services directly stemming from the program?

These are the outputs of the activities that you listed earlier. For each activity, ensure you understand what output they relate to. Oftentimes, outputs may feel redundant to program activities. However, the link between conducting the activities and the outputs being achieved can break for a variety of reasons. It is therefore useful to separate the two. Sometimes, outputs can be passive restatements of activities. Example: The vaccination reminder program may identify “Text reminder about the vaccination camp against malaria is sent to parents” as an output. - What are the real changes in people’s lives that result from the achievement of the outputs? What will lead to the achievement of the goal of the program?

Identify the outcomes that are directly linked to the outputs that you listed. These may be receipt of the service by the target population, such as “parents receive text reminders”. They are often changes in people’s knowledge, attitudes, behavior, and/or living conditions. Example: The vaccination reminder program may identify “Parents take children to the vaccination camp” as a direct outcome of the output from the earlier example. To link that outcome to the overall goal, the program may identify “Children are vaccinated against malaria” as a final outcome.

These boxes are called the nodes of the ToC. Refer to the section below on structuring these nodes in a systematic manner. It may take several iterations until you and your team find a structure that works. Generally, we suggest to work with the following norms:

- Arrange the TOC left to right (horizontally) to capture the program from inputs to impact.

- Try to capture different stakeholders and/or work streams in different rows if possible. For example, a program might engage different stakeholders through policy-advocacy as well as direct implementation in communities, with frequent interaction between the two (e.g. through sharing of case studies). Arrange these two work-streams below one another. In that way you will be able to show how the work-streams interact.

- Indicate the time component at key junctures. Are long term outcomes expected to take 5 minutes, months, or years to manifest at the goal levels?

These arrows represent causal links, i.e., the node the arrow starts from directly causes the node the arrow ends in (activities ➞ outputs ➞ outcomes ➞ goal).

a. Be sufficiently detailed while also being concise.

Review the linkages in the ToC and verify that there are no missing nodes in its causal chains. If there seem to be too many nodes, review the identified activities and outputs. Are all of them essential to the ToC? Are there activities that are similar enough and can be grouped together as part of a larger workstream? How about the outputs?

b. Be specific.

Descriptive and precise nodes are more valuable than general nodes. For example, “Communications Team translates the reminder text to Hausa” is a better activity statement than “Reminder texts are translated”.

c. Ensure that statements follow proper syntax.

Activities for example should always be formulated in active tense. Outputs are generally phrased in passive tense. Additional guidelines on syntax that may further improve the clarity of your ToC can be found in the guidance document from Global Affairs Canada.

d. Label the nodes with alpha-numbers so that they can be easily identified later on.

You could just use numbers to label nodes. In that case, minor changes to the ToC may require you to renumber all nodes, though. For this reason, we recommend that you use an alpha-numeric numbering scheme (A.1,A.1.1,A.2, etc.) to label nodes and linkages.

e. Visualize feedback loops by linking downstream nodes back to those further upstream.

Feedback loops are generally important in programs that take systematic approaches to broad problems. Feedback loops allow you to visualize the complexity and interactions of program components. For example, creating an alumni community could link back to student recruitment for a private skills training program.

| Category | Definition and Notes | Examples |

| Input |

| Funding, people, material |

| Activity |

| Active verbs such as: procure, hire, build, monitor

|

| Output |

|

|

| Immediate Outcome |

|

|

| Intermediate Outcome |

|

|

| Ultimate or Final Outcome |

|

|

Note: This table leverages the definition from Global Affairs Canada (GAC) as defined in the results-based management guidelines found here.

Next steps

A well-designed theory of change is a crucial first step in developing a program. Any organization can develop a theory of change – critical thinking and a deep knowledge of the program and context are all that is required.

Guide

Not sure where to go from here? Use our guide to frame a question and match it to the right method.

Theory of change case study

How a theory of change helped set clear monitoring and evaluation priorities for a handwashing program in the Philippines